The once-teeming waters of the Yangtze River now whisper a haunting elegy for a lost goddess. The Baiji dolphin, revered as the "Goddess of the Yangtze" for centuries, has become a spectral reminder of humanity's fraught relationship with nature. Its extinction—or what scientists grimly call "functional extinction"—stands as a chilling testament to how quickly we can unravel the threads of biodiversity when profit and progress steamroll ahead unchecked.

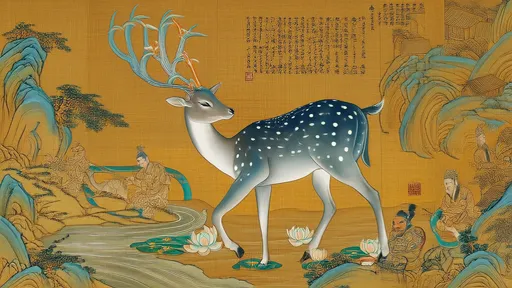

For generations, fishermen along the Yangtze spoke of the Baiji with a mixture of awe and superstition. Its pale, nearly translucent body slicing through muddy waters inspired legends. Local lore held that the dolphins were reincarnated princesses, their elongated beaks resembling the flowing sleeves of Han dynasty nobility. The Baiji wasn't merely an animal; it was a living embodiment of the river's soul, a celestial guardian that had navigated these currents for 20 million years before humans carved their first settlements along the banks.

The autopsy of this extinction reveals multiple culprits. Industrialization strangled the Yangtze with concrete and chemicals. The Three Gorges Dam, that modern marvel of engineering, fractured the Baiji's habitat like a hammer through porcelain. Ship propellers diced through their sonar frequencies, leaving the near-blind creatures disoriented and vulnerable. Fishermen's nets became inadvertent death traps. Each stressor alone might have been survivable, but together they formed a noose that tightened year after year until the last confirmed sighting in 2002—a lone individual swimming against the current of oblivion.

What makes the Baiji's disappearance particularly harrowing is its cultural weight. Unlike obscure beetles or uncharismatic fungi, this was a creature woven into China's artistic and spiritual tapestry. Ming dynasty porcelain depicted its sinuous form. Ancient poets compared its movements to calligraphy strokes made liquid. When the Baiji vanished, it wasn't just a species that was lost—it was a living bridge between humans and their environment that snapped abruptly.

The Yangtze today serves as a grotesque diorama of what happens when warnings go unheeded. Despite the Baiji's dramatic decline in the 1980s—when surveys found barely 400 individuals—conservation efforts were underfunded, poorly coordinated, and ultimately too late. The Baiji's smaller cousin, the finless porpoise, now follows its tragic trajectory, with populations plummeting below 1,000. The river has become a case study in cascading ecological failure: algal blooms choke the water, overfishing empties its depths, and chemical runoff creates dead zones where nothing survives.

Scientists who dedicated their careers to the Baiji speak with the hollowed-out grief of archaeologists watching a museum burn. Dr. Wang Ding, China's preeminent cetacean biologist, spent thirty years tracking the species' decline. His field notes read like a chronicle of despair: "1997 survey—23 individuals sighted... 2006 expedition—none detected." The international conservation community now uses the Baiji as shorthand for preventable extinction, a cautionary tale taught in graduate programs alongside the passenger pigeon and the Tasmanian tiger.

Yet within this tragedy glimmers a perverse hope. The Baiji's memorial—a somber statue overlooking the Yangtze in Wuhan—has become an unlikely pilgrimage site. Schoolchildren leave origami dolphins at its base. Environmental lawyers cite its extinction in lawsuits against polluting corporations. The Chinese government, stung by international criticism, has implemented stricter protections for remaining species. In death, the "Goddess of the Yangtze" may accomplish what living Baiji could not: forcing humanity to confront the true cost of its dominance.

The river keeps flowing, heavy with silt and memory. Barges still churn through waters that once parted for pale dorsal fins. Perhaps the ultimate lesson of the Baiji lies in its silence—a reminder that extinction isn't a single dramatic event, but the slow accumulation of compromises, each seemingly insignificant until the day we wake up to find that magic has left the world. The dolphins won't return, but their absence echoes louder than any conservation slogan, a primal scream from the depths of the Anthropocene.

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025