In the annals of Japanese literature, few creatures have loomed as large—while remaining so deliberately small—as the nameless feline narrator of Natsume Soseki’s I Am a Cat. This sardonic, whiskered chronicler of human folly doesn’t merely witness the foibles of Meiji-era intellectuals; it dissects them with claws sheathed in velvet irony. The novel, serialized between 1905-1906, unfolds as a series of vignettes where professors, artists, and bourgeois strivers parade their pretensions before the unimpressed eyes of a creature who considers them "neither useful nor ornamental."

What makes this particular cat so subversive isn’t just its wit, but its vantage point. Perched on verandas and tucked beneath kotatsu tables, it occupies the literal margins of human society—a positioning that mirrors Soseki’s own fraught relationship with Japan’s rapid modernization. Having studied in London during the peak of British imperialism, the author returned to a Tokyo where Western-style brick buildings mushroomed alongside persimmon trees, where men debated Spencer’s social Darwinism over matcha served in Bavarian porcelain. The cat, like Soseki himself, becomes a conduit for examining cultural dissonance.

Consider the novel’s opening gambit: "I am a cat. As yet I have no name." This deliberate anonymity—this refusal to be christened by the humans it observes—establishes the narrator’s radical autonomy. While the feline occasionally partakes in stolen kamaboko or warms itself by the brazier, it never internalizes the values of the household. The cat’s commentary operates like a kōan, using apparent simplicity to unravel complex truths about mimicry and authenticity. When the pretentious scholar Mr. Kushami pontificates about "the Oriental sublime" while fretting over his receding hairline, the irony isn’t lost on those vertical-slit pupils.

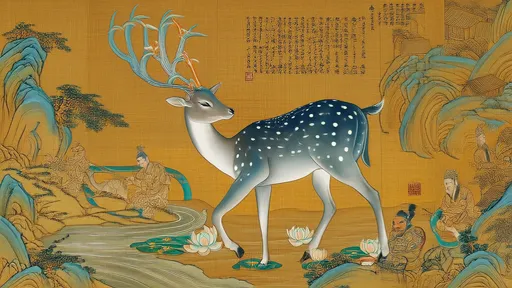

Soseki’s genius lay in recognizing that cats, in Japanese folklore, already carried liminal significance. Unlike dogs—symbols of loyalty in both East and West—cats were trickster figures: the bakeneko of Edo-period kaidan, the shape-shifting companions of witches. By grafting this folkloric ambiguity onto a contemporary setting, he created a narrator capable of exposing modernity’s contradictions. The cat notices how Mr. Kushami’s daughter practices piano sonatas with metronomic precision but cannot distinguish a sparrow’s song from a bush warbler’s. It observes neighbors who replace ancestral altars with gramophones, playing Gilbert & Sullivan records off-key.

This tension between tradition and progress manifests most acutely in language itself. The cat’s narration oscillates between classical kanbun phrasing and vernacular speech, between quoting Confucius and mocking German philosophical jargon. One memorable scene describes a scholar’s thesis as "a sort of semantic tempura—battered Western concepts fried in the grease of Japanese syntax." Such linguistic play wasn’t merely comic; it mirrored the real struggles of Meiji intellectuals to articulate new ideas within inherited frameworks. The cat, of course, remains blissfully unconcerned with this dilemma, its own "meows" requiring no translation.

Modern readers often miss the novel’s political undercurrents. The cat’s disdain for the bourgeois intellectuals’ passivity carries echoes of Soseki’s 1911 lecture "The Civilization of Modern-Day Japan," where he warned against "externally imposed enlightenment." Through feline eyes, we see characters who quote Mill and Kant but fail to intervene as landlords evict tenants or as rickshaw pullers collapse from exhaustion. There’s a particularly chilling passage where the cat watches children throwing stones at a stray dog—an allegory for Japan’s imperial ambitions that Soseki, ever the subtle critic, lets linger without explication.

Yet for all its satire, I Am a Cat harbors profound melancholy. The narrator’s final drunken plunge into a water jar—described with eerie serenity—reads like a quiet indictment of an era hurtling toward unseen precipices. Soseki, who would later write Kokoro with its themes of isolation and generational rupture, seems to mourn through his feline proxy the loss of something ineffable. Perhaps it’s the ability to simply be, unburdened by the weight of "civilization and enlightenment." The cat, after all, never aspires to be anything more than what it is: a creature content to nap in sunbeams while humans fret themselves into irrelevance.

Today, as we navigate our own age of dislocation, Soseki’s cat feels unnervingly contemporary. Its detached amusement at human self-importance, its skepticism toward uncritical adoption of foreign ideologies—these resonate in an era of algorithmic governance and influencer culture. The novel endures not because it offers answers, but because it privileges the act of observation over participation. Like the cat watching goldfish in their bowl, we’re reminded that sometimes the most radical act is to simply see, and in seeing, understand.

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025