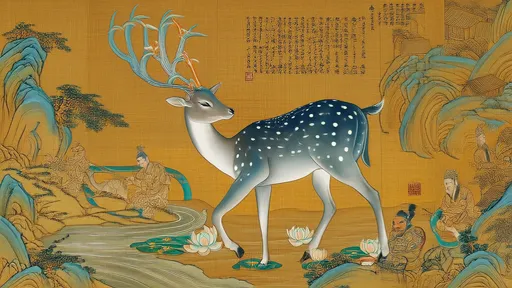

In the annals of Chinese art history, few rulers have left as indelible a mark as Emperor Huizong of the Song Dynasty. A patron of the arts, a calligrapher, and a painter in his own right, Huizong’s reign (1100–1125) heralded a golden age of court painting. Among the many treasures attributed to his imperial workshop, one motif stands out for its exquisite detail and lifelike precision: the jade mantis. This seemingly humble subject, rendered with astonishing realism, offers a key to understanding the broader aesthetic and philosophical underpinnings of "academy-style" painting.

A Monarch’s Obsession with Nature

Huizong’s fascination with the natural world was not merely artistic—it was political. The emperor saw himself as a mediator between heaven and earth, and his paintings of flora and fauna were imbued with cosmological significance. The jade mantis, a creature often overlooked in classical Chinese art, became an unlikely muse. Unlike the majestic eagles or soaring cranes favored by earlier dynasties, the mantis—delicate, predatory, and almost otherworldly in its stillness—embodied the Song court’s obsession with "life-drawing."

Surviving scrolls attributed to Huizong’s workshop depict the mantis with near-scientific accuracy: the serrated forelegs poised to strike, the triangular head tilted as if tracking prey, the translucent wings folded like pleated silk. This level of detail suggests that court painters worked from live specimens, possibly kept in the imperial gardens. Historical records mention Huizong’s menagerie of exotic insects and birds, which served as models for his artists. The jade mantis, with its luminous green carapace, would have been a prized subject—a living jewel to be immortalized on silk.

The Paradox of Control and Spontaneity

What makes these paintings extraordinary is their tension between rigor and vitality. Huizong’s academy enforced strict compositional rules: every brushstroke was measured, every shade of mineral pigment calibrated. Yet the mantis seems to quiver with life, its antennae rendered with hair-thin lines that defy the stiffness of traditional outline techniques. This illusion of spontaneity was achieved through a revolutionary method—layering washes of color over faint charcoal sketches, a technique akin to Renaissance sfumato. The result was a creature that appeared to breathe within the confines of the scroll.

Art historians have noted that Huizong’s mantises often perch on branches of flowering plants, their claws delicately gripping stems painted with the same precision as the insects themselves. This juxtaposition of fragility and latent violence—the mantis is, after all, a predator—mirrors the emperor’s own worldview. In his treatise Xuanhe Painting Manual, Huizong wrote that "the smallest blade of grass contains the principles of the universe." The jade mantis, both jewel and killer, became a metaphor for the Song court’s precarious balance of refinement and ruthlessness.

A Legacy Beyond the Brush

The fall of the Northern Song in 1127 scattered Huizong’s artists and collections, but his aesthetic principles endured. Later dynasties would emulate the "jade mantis style," though none matched its fusion of technical mastery and philosophical depth. Modern scholars using multispectral imaging have discovered underdrawings beneath the painted surfaces—grids and compass-drawn circles that reveal the geometric foundations of these seemingly organic compositions. Even in its meticulous construction, Huizong’s art concealed its own artifice.

Today, as museums digitize these fragile works, new generations can appreciate how a 12th-century emperor transformed a garden pest into high art. The jade mantis endures not just as a masterpiece of observation, but as a cipher—a tiny, green key to unlocking the mind of China’s most enigmatic artist-emperor.

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025