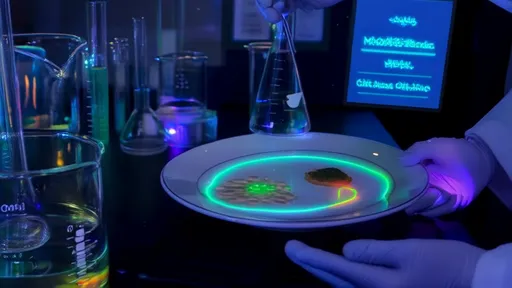

The culinary world stands on the brink of a revolution, one that merges cutting-edge technology with the age-old art of flavor. Virtual taste labs are pushing boundaries by using electrical signals to simulate exotic dishes, offering a glimpse into a future where gastronomy transcends physical ingredients. This innovation isn’t just about novelty—it’s a radical reimagining of how we experience food, culture, and even memory.

At the heart of this breakthrough is the concept of electrogastronomy, a field that manipulates taste receptors through precise electrical stimulation. By targeting specific areas of the tongue and nasal passages, scientists can mimic the sensation of eating without a single molecule of food entering the mouth. Imagine savoring the fiery complexity of a Thai tom yum soup or the umami richness of Japanese miso black cod—all while your plate remains empty. The implications for dietary restrictions, space travel, or even climate-conscious eating are staggering.

One lab in Kyoto has already mastered the simulation of katsuobushi—the smoked, fermented tuna central to Japanese dashi broth. Their device delivers a sequence of micro-pulses to recreate the fish’s smoky depth, followed by a delayed "umami wave" that mirrors its lingering aftertaste. Test subjects report an uncanny realism, though some note a faint metallic undertone—a reminder that the technology is still in its infancy. Meanwhile, researchers in Stockholm are experimenting with virtual pairing, using scent diffusers and electrode arrays to "serve" simulated saffron risotto alongside projected images of Venetian canals.

The cultural ramifications run deep. For diaspora communities, such technology could evoke ancestral flavors otherwise inaccessible due to scarce ingredients. A Venezuelan expatriate might relive the taste of pabellón criollo using a handheld device, its electrical patterns derived from scans of the actual dish. Yet critics argue this risks reducing cuisine to mere data points, stripping away the social rituals of cooking and sharing meals. There’s also the philosophical question: If no plant was harvested, no animal raised, no spice traded—can the experience truly be considered "eating"?

Commercial applications loom large. Food conglomerates are investing heavily in flavor algorithms, aiming to patent signature taste profiles. Imagine downloading a celebrity chef’s signature dish as easily as a music track. But this raises ethical concerns: Who owns the rights to culturally significant flavors? Could the digital replication of a traditional Maori hangi feast amount to culinary appropriation? Regulatory bodies are scrambling to define boundaries in this uncharted territory.

Perhaps most intriguing is the technology’s potential to create impossible flavors—combinations that don’t exist in nature. Early experiments suggest the human palate can perceive "layered tastes" when stimuli are precisely timed: a burst of simulated mango followed milliseconds later by virtual wasabi creates a wholly new sensation. Some researchers speculate about "haute electrocuisine" restaurants where diners experience ever-shifting flavor symphonies, their taste buds conducting an orchestra of currents.

As with any disruptive innovation, the path forward is peppered with challenges. The current hardware—often bulky mouthpieces or tongue pads—falls short of seamless integration into daily life. There’s also the matter of individual biological variability; a signal sequence that evokes truffles for one person might register as mere saltiness for another. And while the technology can simulate taste and aroma, it cannot yet replicate texture—the crunch of tempura or the silkiness of foie gras remains elusive.

What emerges is not just a new way to eat, but a new lens through which to examine our relationship with food. These virtual taste labs are doing more than mimicking meals—they’re challenging fundamental assumptions about nourishment, pleasure, and cultural identity. As the technology matures, it may well redefine not just what we eat, but what eating means.

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025